In the Triangle of Fan Culture, Comedy, and Conceptual Art

Ben Davis on Signifier, Signed

In conjunction with the exhibition Paul Schmelzer: Signifier, Signed at Macalester College (March 23–29, 2017), the Law Warschaw Gallery commissioned the following essay by author, critic, and Macalester graduate Ben Davis.

I think Paul is a little sheepish about this show, so let me just begin by confessing that I think that I am, in part, to blame for putting him in this position. Without my suggestion, he may not have put himself through this.

I became familiar with Paul Schmelzer as an important editor and advocate for outspoken artists. For years he has run the Walker Art Center’s website. The Walker has been pioneering among museums in using its institutional clout to create a serious online publishing space. Among other things, Paul has used the Walker site to get artists, famous and not-so-famous, to pen “Artist Op-Eds” about current events.

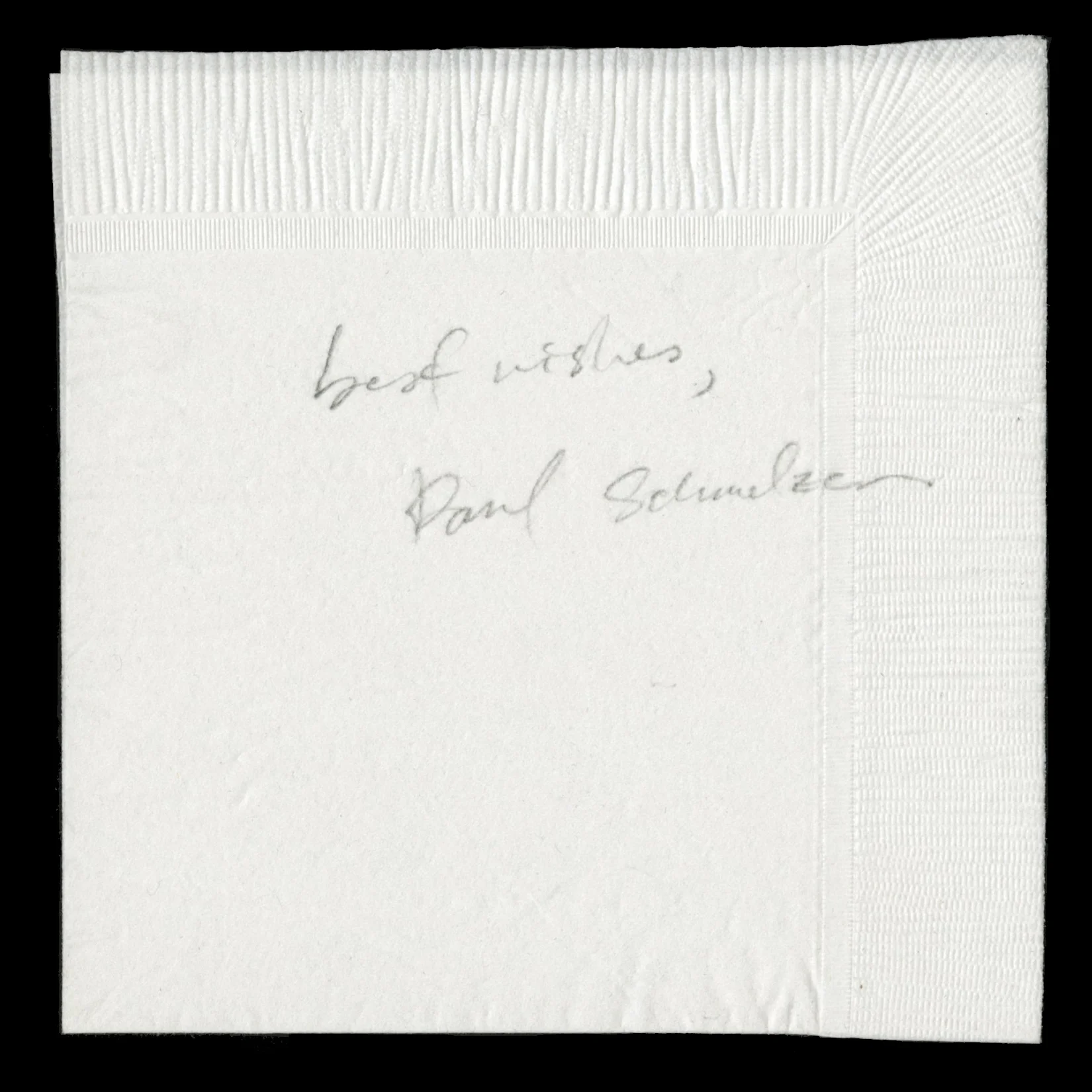

Paul Schmelzer, as signed by Matthew Barney

Last time I saw him, he pressed into my hands a bright yellow pamphlet he had made from one of these op-eds called “A Circle of Blood,” by the well-known African-American painter Jack Whitten. It is about Whitten’s experiences growing up in the segregated South, and it begins with a stark question: “What justifies staying in the studio when the outside world is constantly testing my faith in art?”

I mention this because Paul, of all people, knows the possible critique of this project that it is a little trivial, a little bit of an odd thing to be launching into the world. So let me tell you why I egged him on, and what I think its value is.

I first met Paul a few years ago when he organized a conference on art writing in the digital era at the Walker, for which I gave a talk. I also happen to be a Macalester grad (’01), and as such have been invited back to the Twin Cities to speak. I think we were having a beer one afternoon with Greg Fitz, the former head of the Law Warschaw Gallery, when Paul brought up, as an aside, his long-running personal project to get celebrities to autograph his own name, “Paul Schmelzer.”

Signed, Signifier wasn’t in the finished form that it is here. It was just a funky Blogger site and a title, really just a thing he was doing with his stray time. And it is exactly because I knew Paul as this serious figure that it delighted me. I think I laughed out loud. (If you are thinking to yourself, “Is this a joke?,” one answer is, “Yes! Yes, it is!”)

Somehow or other, the idea emerged of showing Paul’s trove of “Paul Schmelzers” here: Matthew Barney’s “Paul Schmelzer,” Noam Chomsky’s “Paul Schmelzer,” Yoko Ono’s “Paul Schmelzer,” Henry Louis Gates’s “Paul Schmelzer,” Kim Gordon’s “Paul Schmelzer”…

When I was at Mac, the head of the Art Department was the late Don Celender, one of the pioneers of correspondence art. Roberta Smith once called Celender the “pollster laureate” of Conceptual art, because he liked to work in the form of the survey.

Celender did projects like the Daytime Television Actors Art Preference Survey (1998), polling soap actors about what artist from history they’d like to see cameo on their show, and showing the responses. For his Business/Art Survey (1981), he sought out the owners of businesses with names like “Artistic Homes, Inc.,” “Artistic Silk Floral Designs,” and “Artistic Dental Ceramics,” cataloguing their answers to the question of what the word “artistic” meant to them, which were fascinating both in how close and how far they were to the way art is talked about in galleries and museums.

Celender’s works were funny but not mocking. Their main spirit was curiosity. They were literally and figuratively about correspondence, about the interesting energy that emerged when rarified ideas of fine art came into dialogue with the broader ways people think about culture and creativity.

Paul’s project hits a similar note for me, somewhere in the triangle of fan culture and comedy and conceptual-art passion project.

In general, contemporary art is truly obsessed with names. Half of the fatiguing atmosphere of an art opening is that everyone is glancing furtively at the wall labels to confirm that they have the right frame of reference before they speak. This, in turn, makes the whole scene quite unlovable. It gives the impression that rather than representing any authentic pleasure, art is a field for the exercise of pseudo-connoisseurship, a game of competitive matching of difficult-to-identify art objects with authors and references, to prove you are better educated or more in the know.

Raphael Rubinstein has a wonderful little book, The Miraculous, which tells the history of art, post-1960s—when art got really slippery and hard to define—in a series of short vignettes. The book’s gimmick is that he tells the story of each of the artists’ pieces without their names, so all you have is a little account of something someone or other did, poetically told.

And the effect is pretty liberating. You realize that you don’t actually need to know anything about “David Hammons” or “Cindy Sherman” in order to love what they did. If all you heard about was the man who took to the street one day to sell snowballs in winter, or the woman who set up photos of herself meticulously costumed to look like old movies, you’d think, “what a funny story!” or “what an interesting person!”

At any rate, the ultimate reference needn’t be professional, the “commentary on the Duchampian readymade” or the “critique of the construction of identity.” These artworks might also be those things—but before we remove them to too rarified a level, we should first of all see them as relatable.

These types of works are not feats of oil paint or woodworking, but they nevertheless connect to a kind of creativity that everyone is actually familiar with, without necessary valuing it: the eccentric routines and unexpected hobbies and oddball affectations that people adopt to make sense of or cope with the stress and chaos of contemporary life.

If we could see contemporary art more like that, in general, and less as if its ultimate goal had been to end up in a museum and talked about by museum people—as a valuable thing next to a well-known name—I firmly believe people would like contemporary art more.

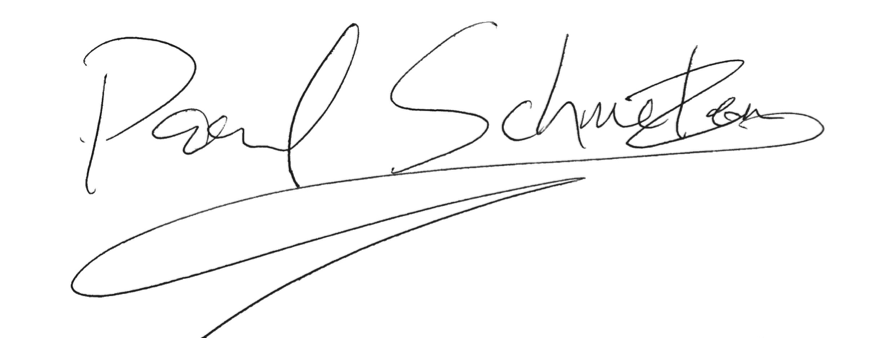

I know there is more to get from Signifier, Signed. There is a whole psychoanalysis of signatures. Have fun comparing how one figure signs Paul’s name versus another, and try to guess what it says about them, and just how bemused, or exasperated, or clueless they were when they got out their pen.

Paul Schmelzer, as signed by Ben Davis

All these people are famous people, in one way or another on a pedestal. Paul is both stealing a little of their celebrity and deciding not to be too cowed by it, to trust in the value of his own personal game. It is specifically about tweaking the awed way we elevate creative celebrity—which also means that treating it in too exalted a way is going to undo what is charming about it.

I know this is paradoxical to say of a show that is literally just the artist’s name written over and over again, but I encourage you not to think about Signifier, Signed as the product of too much artistic ego. This show, for me, is about being attentive to the kind of creativity that bubbles up in the holes around capital-A art.

Like when you are sitting across from a friend and they mention to you this one funny thing they just happen to have been quietly doing, for years, without making much of it.

Life is full of these eddies of creativity, somewhere between making art and just making sense of your place in the world. Once you realize that, you might realize that you also are a Paul Schmelzer.

Ben Davis is a New York–based art critic and author of 9.5 Theses on Art and Class. He is currently national art critic for artnet News.